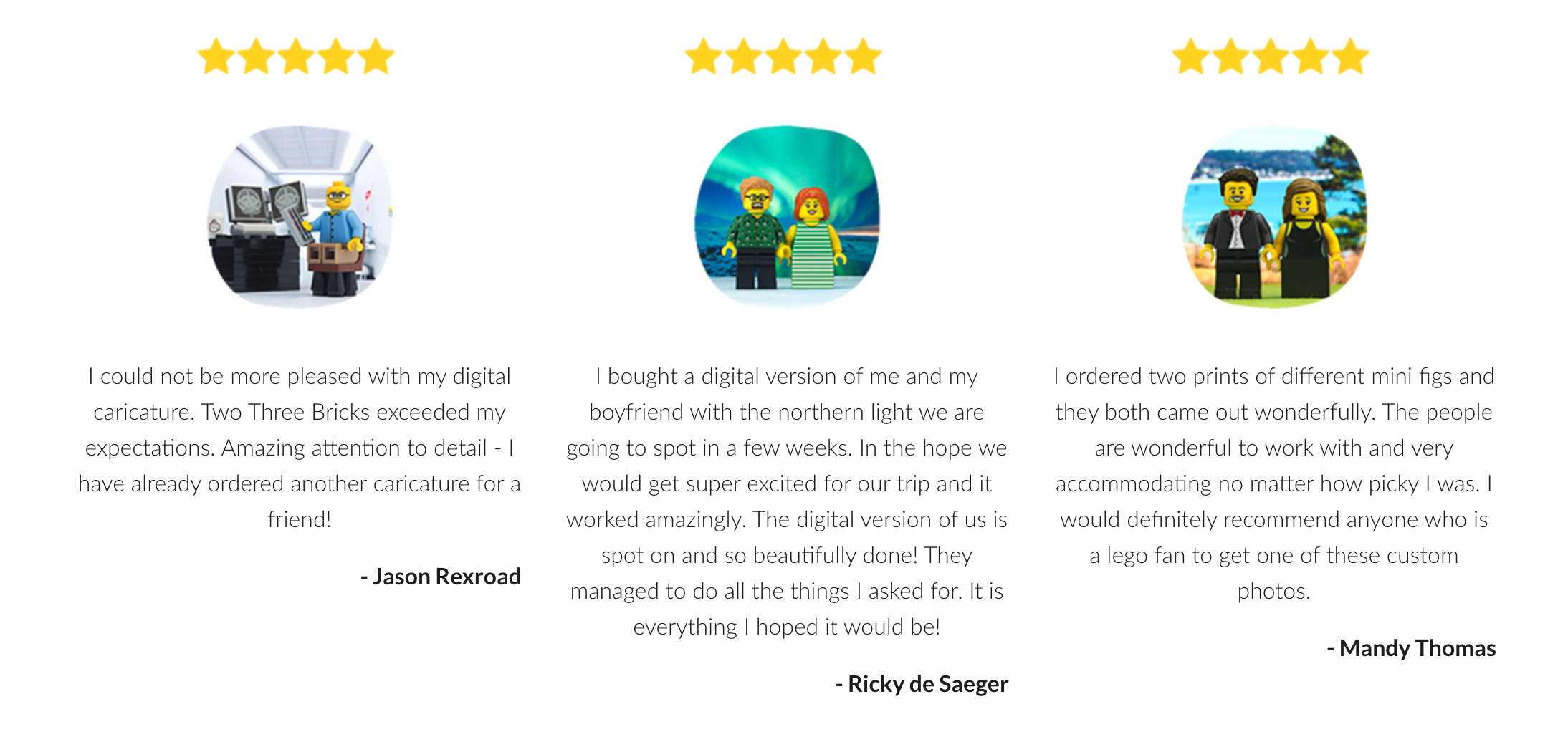

What are LEGO caricatures?

Send us a photo, and let us imagine how you'd look like as a LEGO Minifigure. This makes for the perfect gift for your loved ones, or if you just want see how you'll look like in LEGO.

We allow you to customise each and every detail, down to your favourite hobbies and outfits.

Let us make you look like you! 👋

Two ways to share the love ❤️

We'll deliver a high-resolution copy delivered via email, suitable for prints up to 12"x8", within 14 days of your order.

Get Digital

We'll send physical prints on various mediums including photo cards and wood panels, using only high-quality printing methods.

Get Prints